Myth of the Low-Maintenance Landscape

In the survey we send to all new and prospective clients, one of the most frequently requested goals is a “low-maintenance landscape.” If all time spent tending a landscape were equal, that might be something we could quantify. But it isn’t.

High and low are simply not very good descriptions for the range of tasks different landscapes require to stay in a desired state. Maintenance isn’t just labor. It’s time, knowledge, and tools. These are resources not everyone has, or wants to have, in equal measure.

An Eight-Year Experiment in “Low Maintenance”

Eight years ago, I began my own experiment with a so-called low-maintenance garden. I sheet-mulched about 150 square feet of lawn in the hellstrip in front of my house, the space between the sidewalk and the street, and planted mostly native, drought-tolerant species with low fertility needs.

My intention was to not baby the plants. I wanted them to battle it out. I added no compost and no irrigation. I hand-watered newly planted sections for a few weeks, but after the first season of planting, I stopped regularly watering. I mulched only once, right after planting, with shredded leaves and woodchips.

The weeding needs tapered off over time, dropping dramatically after the third season, when most plants reached maturity. About the same time, the battle for space and survival began in earnest. Some plants self-seeded, and others spread by rhizomes. Every year, the garden has been full with plants that I have chosen, but not necessarily where I put them.

What Maintenance Actually Looks Like

This spring, it took me about 15 minutes to weed the front strip. Over the summer, I probably spent another 20 minutes total, mostly pausing to pull an unwanted volunteer as I walked past.

Late fall, I spent about an hour pulling the turf grass that constantly tries to colonize the beds, cutting back aggressive seeders, and collecting seed from early bloomers to propagate or share with friends. The leaves that fall in the beds stay there all winter. I’ll spend another hour or so in the spring removing turf grass and cutting back old stalks and seed heads.

All told, that’s about three hours a year.

A Garden That Changes Year to Year

Every year has been different. In dry years, butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) dominates, its vibrant orange flowers shimmering against my coral-red house from halfway down the block. For several years, hoary vervain (Verbena stricta) took over, creating a tall, misty purple screen along the road.

I intervene at key moments, like cutting down vervain before it goes to seed, but mostly I let the plants fend for themselves. It’s a curated garden, not a controlled one. In recent years, I have chosen to let some volunteer plants establish where they appear. This has increased the variety of plants in unexpected ways. I enjoy it every year, including the mystery of what it will look like next season.

A Long View: 2018–2024

2018

The first iteration included a swath of bulbs to make the space legible in early spring. The grape hyacinths have shrunk but still return each year.

2019

A balanced mix of butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), salvia (Salvia x sylvestris), nodding onion (Allium cernuum), hoary vervain (Verbena stricta), and Zagreb coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata).

2020

Salvia declined; nodding onion and butterfly weed thrived. A great year for monarch caterpillars.

2021

Hoary, or woolly vervain (Verbena stricta), is a clumping perennial that also self-seeds aggressively. It is a host plant for the common buckeye butterfly and others. It began to dominate – even seeding itself into the cracks of the sidewalk and driveway.

Butterfly weed struggled during wet years but has persisted. I planted this for its durability and habitat value, not for its color, but I have enjoyed the vibrant clash of reds, purples, and bright orange much more than I expected.

2022

An extension of the strip where spotted horsemint (Monarda punctata), obedient plant (Physostegia virginiana), nodding onion (Allium cernuum), thin leaf mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginiana), and hoary vervain (Verbena stricta) are battling it out. 2023 was a three-way tie between the obedient plant, mountain mint, and vervain.

2023

Butterfly weed is also a double-survivor: both a clumping perennial and aggressive self-seeder. I sometimes add signs in the fall encouraging pedestrians passing by to take seed pods when they start opening.

Leaving seedheads relieves some labor needs while providing habitat, self-seeding for desired plants, and visual interest. Wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) makes one of my favorite seed heads. In recent years, it has become largely outcompeted.

A super wet year. Impressively, the butterfly weed still had a strong presence. The Zagreb coreopsis exploded, and the liatris spicata that had been floundering a bit the last few years was spectacular.

2024

Violets and blue wood aster filled gaps, creating a lush early-season display.

Another welcome volunteer is a blue wood aster (Symphyotrichum cordifolium) that initially appeared in the foundation plantings and has seeded into the hellstrip. It explodes in an astounding number of blooms in full sun, especially with some late summer rain.

Why This Works for Me

This version of a “low-maintenance” garden works for me because:

- I can recognize the plants I’ve planted in every season, and I identify the volunteer seedlings I don’t recognize,

- I enjoy weeding and transplanting, and

- I’m happywith (even excited about!) a garden that looks different every year.

For someone who wants uniformity or isn’t confident in identifying plants, this garden could be a constant source of frustration.

Beyond High vs. Low Maintenance

Why do we love dichotomies, when so often two-dimensional thinking fails us?

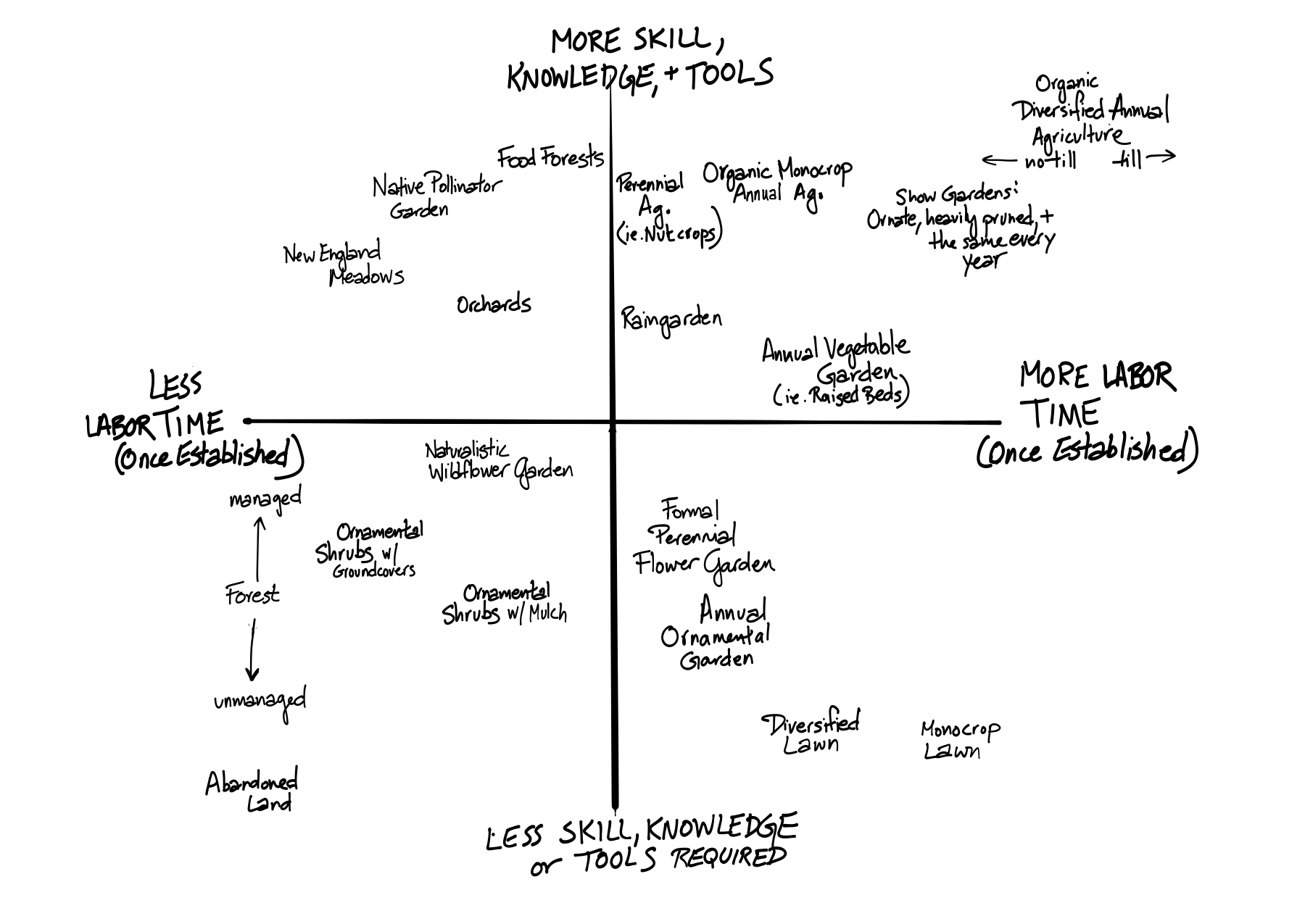

Below is my attempt to move beyond “high” versus “low” maintenance by mapping different landscape types across two axes: labor time (once established) and the level of skill, knowledge, and tools required. Even after expanding from a simple linear spectrum to a quadrant graph, it’s still difficult to fully capture the range of maintenance demands different landscapes impose.

The diagram highlights a few important truths. A highly formal perennial garden paired with a manicured monocrop lawn requires sustained, ongoing labor to resist constant ecological change. A forest, by contrast, may require very little intervention year to year—but actively managing a forest can demand intense bursts of labor and specialized tools once a decade.

Looking only at average labor time misses these differences. We would benefit greatly in long-term planning by approaching maintenance with a much more nuanced lens.

This kind of graph still can’t capture everything. It flattens important variables like seasonality, climate, and scale. Perennial agriculture may require less labor overall than annual vegetable production, but that work is differently distributed throughout the year. Tasks like pruning, harvesting, or pest control are time-intensive and only effective when done at the right moment.

Maintenance isn’t just about how much work is required. It’s about when that work happens, who can do it, and what kinds of knowledge and tools it depends on.

Although a lawn requires far more annual labor than my pollinator strip, it demands much less decision-making. Many landscaping companies don’t hire or train staff with the plant knowledge needed to maintain diverse ecological gardens, which, unfortunately, makes these dynamic and resilient landscapes expensive or inaccessible.

The Missing Dimension: Pleasure

For those of us who care for our own landscapes, the real measure of “low maintenance” may be something that can’t be graphed at all: pleasure.

If you find mowing meditative and weeding tedious, a diversified lawn will feel lower-maintenance for you than a perennial garden. If you dread the noise and smell of mowing, switching to an electric mower or a reel mower might change the equation entirely. If you enjoy the thrill of a garden that looks different every year, let the plants respond to their environment and skip the nuisance of irrigation and regular applications of fertilizer.

A landscape that feels engaging, fulfilling, and meaningful to you will be a pleasure to maintain—and will be time well spent, no matter how much time it takes.

—Rachel Lindsay, Head of Ecological Landscape Design, Senior Designer, and worker-owner

Comments (0)